4. THE SIEGE OF MONTSEGUR 1243-1244

Following the assassinations of the Inquisitors in Avignonet in May 1242, there were wide spread revolts in Occitania against the French Crown and Catholic authorities. By January 1243 it was all over. The rebellions failed and the leading local overlord Raymond VII, the Count of Toulouse, in whose territory Montsegur fell, signed a final peace treaty with the French King Louis IX. Raymond VII who had rebelled previously, and was until then, a strong Cathar supporter, if not a clandestine believer, was once again forgiven by the King and the Church. But Montsegur was to be destroyed, and Raymond who in the past managed to sidetrack plans of French crusading forays to Montsegur, stood aside this time.

At a Catholic conclave held in Beziers in the spring of 1243, a call to bring down the "synagogue of Satan" at Montsegur was issued. The operation was put under the military command of the King's seneschal of Carcassonne Hugues des Archis, while the church was represented by the Pierre Amiel, the arch-bishop of Narbonne. By Ascension Day in May 1243, on the anniversary of the assassination, warriors from Gascony and the Aquitiaine, buttressed by local troops pressed into service, began to pour into the valley below the pog at Montsegur. Over the next ten months, a total of ten thousand troops would mass beneath the fortress, drawing a tightening perimeter around Montsegur.

MONTSEGUR AS IT MIGHT HAVE APPEARED IN THE SUMMER OF

1243

DURING THE SIEGE ( VIEW FROM THE SOUTH LOOKING NORTH

)

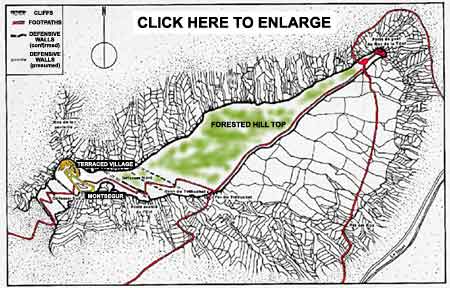

MAP OF

DEFENSE LINES AND

APPROACHES TO MONTSEGUR 1243-44

(click on map to enlarge)

The Cathars had been living within the fortress and in a small

terraced village just beneath the north-eastern slope of the current fortress

wall. Small settlements also dotted the northern face of the pog,

which gently sloped downwards away from the fortress like a camel's back, and

finished at yet another manned outpost known as Roc de la Tour--"Tower

Rock"--before suddenly dropping off into precarious cliffs. The main south-western approach to the fortress was very

steep and protected by several walls. Despite all the

Catholic troops, there were many secret footpaths leading up to the

fortress: messages, troops, refugees and some provisions

continued to infiltrate through the French lines--both into and out of

Montsegur.

Pierre-Roger Mirepoix took command of the defense of

Montsegur. From his own vassals he had a total of seventy

men: 18 battle hardened knights--including the assassins of the

Inquisitors--six light riders and an assortment of infantrymen and

sergeants and two or three crossbow men loaned to Pierre-Roger by

other lords sympathetic to the Cathars. There were at least

another ten independent knights, making an extraordinary concentration

of nearly thirty knights at Montsegur. Other troops, archers and hired mercenaries rounded out the

number of armed defenders at Montsegur to approximately 150 warriors

in total.

There are myths that the Knights Templar came to the aid of the Cathars and that this set them on a long path of final destruction at the hands of the Inquisition in 1307. Many of the descendents of the Templar Grand Master Bertrand de Blanchfort (1156-1169) were Cathar sympathizers based at his family seat a mile from Rennes-le-Chateau, near Carcassonne. The Templars, in fact, did not participate in the Albegensian Crusade--but only because they did not have the available manpower at the time. There is, however, one instant on record where the Templars came not so much to the aid of the Cathars, but fought against the French Crusaders. In September 1213, Templars in the service of the Aragon King Pedro II participated in his failed attack on the French Crusaders of Simon de Monfort at Muret. These Templar actions, however, were motivated more by their allegiance to King Pedro than by any Cathar sympathies.

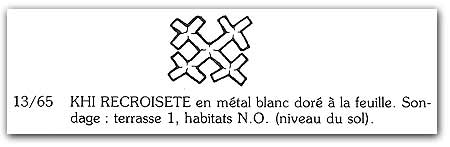

Interestingly enough, in 1965 archeologists digging in the Cathar era strata at the terraced habitations, uncovered an insignia from another crusading monastic order--a so-called Khi Recroisete--made in precious white metal, worn by senior members of the Hospitaller Order of St John.

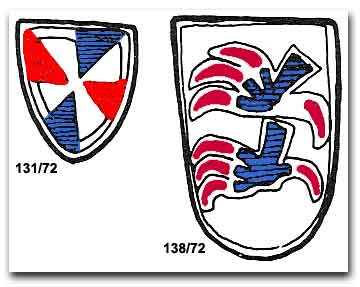

Other coats-of-arms discovered and not successfully identified by the archeologists working at Montsegur:

-

131/72 CLOU DE CEINTURE armorie. Decor d'emaux champleves en forme d'ecu fransais gironne de huit pieces, bleues et rouges opposees deux a deux. Blason non identifie. L.: 18mm, l. : 16mm, ep. : 0.5 mm. Sondage: terrasse 2, habitats N.O., carre G2a42

-

138/72 CHAPE OU BOUCHE DE FOURREAU (?) de dague armoriee. Decor d'emaux cloisonnes en forme d'ecu espagnol portant deux serres de pace. Les ongles sont rouges, les pattes bleues. Blason non identifie. L. : 60mm, l. : 38mm, ep. : 38mm. Sondage : terrasse 2, habitats N.O., carre G2a34

[Groupe de Recherches Archeologiques de Montsegur et Environs (GRAME), Montsegur: 13 ans de rechreche archeologique, Lavelanet: 1981. pp. 104-105.]

Montsegur was relatively self-sufficient with a good reservoir

system of cisterns for water and A metal forge for weapons and an ample

supply of wood to fire it. Meat and dairy products were

not in high demand by the strictly vegetarian Cathars and supplies

continued to trickle in. Furthermore, the pog on which Montsegur is perched, is riddled with

an astonishing network of hidden caves which are still being discovered

and explored today. What role they might have played in penetrating

siege lines is

still an unanswered question.

The civilian population of Montsegur consited of some fifty to one hundred Cathar perfecti and an assortment of refugees, followers, believers, wives, children and other family members, servants, craftspeople and court officials --an estimated total of approximately five hundred people of both sexes and all ages.

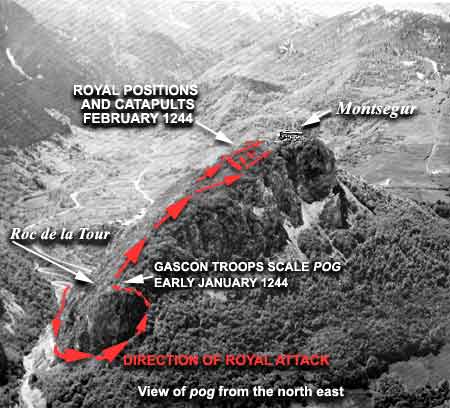

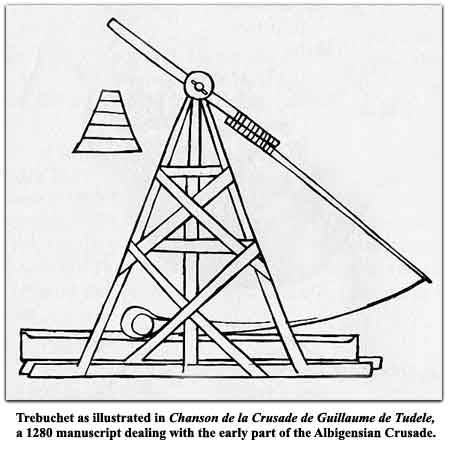

The siege unfolded slowly for the first eight months, with Catholic forces painstakingly attempting to take the slopes of the mountain to position powerful trebuchets -- catapults -- within range of the castle. Yet the slopes proved to be so impregnable that by the end of 1243, the Catholic troops were severely demoralized by their lack of progress. The break came in January 1244, when Gascon mountain troops climbed up the north-eastern tip of the pog in the middle of the night and captured the lowest point of the plateau--the Roc de la Tour. From there, Catholic troops began to effectively fight their way up towards the fortress--capturing positions for a trebuchet and using the resources of the plateau to construct the catapult and mine the stone missiles for it. Today the slopes of the plateau are still dotted with piles of stone missiles shaped in workshops set up by the attacking troops.

After two months, towards the end of February, the Catholic catapult was close enough to launch the stone missiles with deadly accuracy. The progress of the French attack can be charted by the weight of the balls. At first only light stone missiles weighing between 25 and 35 kilograms (55 -- 77 lbs) could be fired from the initial positions established by the Royal forces. By the end of the siege, the troops were close enough to lob 80 kilogram missiles ( 176 lbs) into the inhabited terraces with devastating effect.

Stone missiles uncovered by

GRAME archeologists on the terrace habitations in 1970

The Cathars attempted several sortie counter-attacks to dislodge the crusaders but it was too late--heavy reinforcements had poured up through rear part of the pog and were now dug in. It appears that the majority of the combat fatalities at Montsegur occurred in the months of January and February--in skirmishes on the northern slope and under the increasing bombardment of stone missiles. Again, the Inquisition records give us glimpses into some of the fatalities:

- Knight Jourdain du Mas is given consolamentum under special circumstances in February 1244 --he is in a coma after being struck by a stone missile--and cannot consciously acknowledge the procedure before dying; [Doat 22, 209a, 241a, 281b, 253b.]

- Knight Betrand de Bardenac, given consolamentum before dying "after Noel 1243"; [Doat 22, 209a, 241b, 254b.]

- Sergeant Bernard Rouain, given consolamentum at his death from wounds on February 21, 1244 [Doat 24, 79b.]

- Sergeant Bernard de Carcassonne, consolamentum at his death on February 26, 1244; [Doat 22, 254a - 24, 207a.]

- Pierre Ferrer, Catalan and bailiff of Pierre-Roger Mirepoix, consolamentum upon his death from wounds sustained, March 1, 1244 [Doat 22, 255a.]

- Sergeant Guillaume d'Aragon, participant in the Avignonet assassinations, killed at an undetermined date. [Doat 22, 205a.]

Now under

bombardment, the terraced habitation outside the walls of the

fortress had to be evacuated for the safety of the fortress walls.

By the end of February,

Pierre-Roger understood that there was no hope of relief from the

outside and that Montsegur could not hold out much longer.

GO TO NEXT PAGE:

THE SURRENDER OF MONTSEGUR